At the top of a run they call The Rise, I threw cast after cast. Cast the fly, let the fly swing, let the fly dangle, pump the fly twice, take two steps downriver, repeat. I was looking for the fish of a thousand casts. On about the 420th cast, something different happened. I casted the fly, the fly swung, the fly stopped, and the fly began to swim away. I stayed as calm as I could. I had envisioned this moment 419 times already today, and now it was coming true. I lifted my arm and brought the rod to the left. I came tight to the fish and began to feel her head shake. The fight was on, and I was shaking in my boots. When we finally landed the fish, I was beaming. My first wild Steelhead, something many anglers dream of, but few will ever experience. 1

Steelhead are a species of rainbow trout that leave the relative safety of a river ecosystem and swim downstream until they hit the salty water of the ocean. A fish born in Washington may travel to the island of Japan, up the Kamchatka peninsula of Russia, over to the coast of Alaska, and then back down south to the same Washington river system where it was born. It will then swim up that river to spawn, and then return to the ocean to continue its journey as an anadromous fish. 2

Historically, the most successful runs of Steelhead were found in Northern California, Oregon, and Washington. As you can imagine, human impacts have greatly changed this dynamic. Now, the rivers of British Columbia, Alaska, and Kamchatka (Russia) sustain the most successful runs of wild Steelhead; however these populations are also struggling compared to their historic levels.

Recently, I visited what used to be the stronghold for Steelhead in the Lower 48, the Snake River. The Snake begins in Yellowstone National Park, and flows over 1,000 miles through Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington before it joins the Columbia River. Think back to our friend the Steelhead and the journey she used to embark on. Before the impact of humans (notably colonial settlers) these fish would swim thousands of miles to get their freak on for a few days, then swim back to the ocean. As you can imagine, all this swimming makes for one hell of a fish. One that I certainly love to catch.

But despite their impressive strength and desire to swim, our sweet Snake River Steelhead faced a whole new challenge in the 20th century.

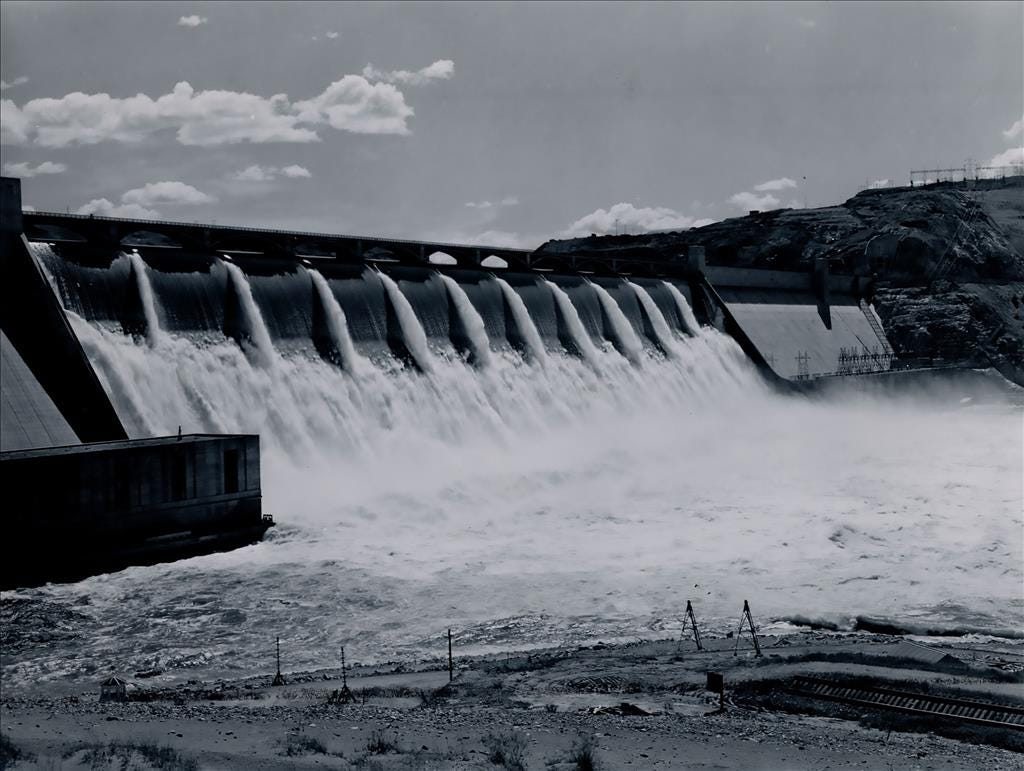

Someone put a big ass wall across the river.

In 1933, Rock Island Dam was constructed in central Washington on the Columbia River. As more people moved to the Pacific Northwest, they needed electricity, and hydropower was seen as the best option. The dam did a great job of providing electricity and a reliable water supply to the growing population of the PNW. But in reality, it did a terrible job of protecting the Steelhead, Salmon, and the indigenous communities that were deeply connected to the land. Nonetheless, the $$$ started flowing and cheap energy plus a booming economy brought millions of people to the region. Soon enough, dams were the best way to provide the power that these folk needed. By 1968, there were four dams on the Columbia River, and by 1975, four on the Snake River. I will not pretend to be naive, the benefits of these dams used to be immense. They provided consistent electricity, year-round water supply, and allowed for goods to travel by boat from the Pacific Ocean all the way to Idaho, making Lewiston Idaho - 465 miles inland - the furthest inland port in the PNW.

These dams were integral in transforming the PNW from the hellishly beautiful ecosystem it was, to the agricultural, manufacturing, and energy hub that it is today.

But, it is now 2024, and myself as well as a large sum of people see a different future. One in which the Snake River is a free flowing river, as mother nature intended it to be. One in which the Steelhead swim freely, the Salmon spawn in their natural habitat, the bears, birds, and other animals reap the benefits of the return of wild fish. And most importantly, the people that call this region home, are lucky enough to experience the ecosystem that they deserve.

What’s so bad about a dam? How does it impact the fish populations?

Dams create a totally unnatural ecosystem. For thousands of years, the Snake River flowed freely from its headwaters to the ocean as a river. With the addition of the dams, this river has turned into a lake. A slow moving, stagnant, and warm body of water that is abnormal to the native species that inhabit it. Historically, the Snake River supported native species of Steelhead, Salmon, Trout, Sturgeon and some 35 other fish species. Each one specifically evolved to live in a coldwater, fast moving, river ecosystem. With the addition of the dams, predators, dam turbines, and hot water have wreaked havoc on the native fish.

Here are some numbers from 2009 - 2019 that will shock you:

Historically, 1.5 million King salmon swam up the Snake River every year. Now? The average is 16,000, nearly a 99% decline.

It gets worse. Back in the day, 600,000 Steelhead made the journey to the Snake River. Today, that number is down to about 19,000 - a 97% decline.

The numbers are staggering and the solution is clear: the dams must come down. Countless other solutions have been tried - transporting fish over the dams, introducing hatchery-raised fish, and countless others, but nothing has worked.

However, you might be wondering “What about the energy, irrigation, and transportation benefits of the dams?”

Thankfully, there’s never been a better time to address these challenges. Reinvesting in energy sources like solar and nuclear can easily replace the lost electricity from the hydropower. Expanding the surrounding rail network will take the place of barge operations. Finally, improving the irrigation systems can continue to provide the surrounding agriculture based communities with the water they need. I’m doing my best to save you the boring details. If you care to really dive in, check out this report put together by a bipartisan coalition of state lawmakers from the PNW.

As I type this, I sit at my desk on the banks of Bellingham Bay. Sadly, I can’t see the ocean. But I do know that in this bay, there are Steelhead swimming. Eventually, each of those Steelhead will return to their birth stream. Whether that stream is five miles down the beach or 5,000 miles across the Pacific ocean, it doesn’t matter to them.

Removal of the dams will require an act of Congress, please don’t let that dissuade you. The best way to help is to make your voice heard. Here is a petition you can sign.

Additionally, if you care to watch a great film about this project, click here.

She sam away during the photoshoot and I never got a shot. I couldn’t care less.

Anadromous = born in freshwater, migrates to the ocean, and returns to the river to spawn.

Amazing writing. The snake river is one of the most memorable rivers in my life, I would love to see the dams removed.

One of the saddest things about living in LA was seeing how the city infrastructure destroyed wildlife. There was a mural in my neighborhood that read “Grizzlies used to walk on Venice beach”. Steelhead also used to run up the LA river, and now it’s basically the world’s largest drainage ditch.

I hope the recently completed dam removals on the Klamath create momentum for other projects.